Important Reads Right Now

Connection to Country

We wrote this article in our first issue of HANDLE and feel it is extremely relevant to publish it again now in our first blog post of 2020 - Connection to Country.

In June 2017 the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects, (AILA), held a remarkable and inspiring event at the Utzon Room, Sydney Opera House, titled Connecting to Country. We listened to some extremely knowledgeable, passionate and influential speakers who discussed their affiliation with the Australian Aboriginal people, their culture and heritage, and how that connection enriches how they live and work.

“I’ve always felt that Landscape Architecture and Aboriginal heritage are such a good fit. As a profession of only 50 years in Australia, we strive to understand the landscape its natural and cultural context and then make the best decisions for that landscape and for society. We live in a country that has an indigenous people that has had 50,000 years of striving to do the same – with great success. We need to do more to develop our appreciation of the Aboriginal heritage and put that knowledge to good use. In this respect Australia has great untapped potential that no other place on Earth can rival. This event is just a small discussion on the way to using that untapped potential.”

Host of SBS program Insight, Jenny Brockie was the perfect MC for the event. She facilitated a spirited, eye-opening and thought-provoking discussion on the topic, which you could tell was close to her heart. The speakers were:

Bill Gammage – Emeritus professor, Humanities Research Centre at the Australian National University. Ros Moriarty – Managing and Creative Director, and John Moriarty – Chairman – Balarinji. Dillon Kombumerri – Principal Architect, Office of Government Architect NSW. Greg Grabasch – Principal of UDLA, Multiple-award winning design studio in Fremantle, W.A.

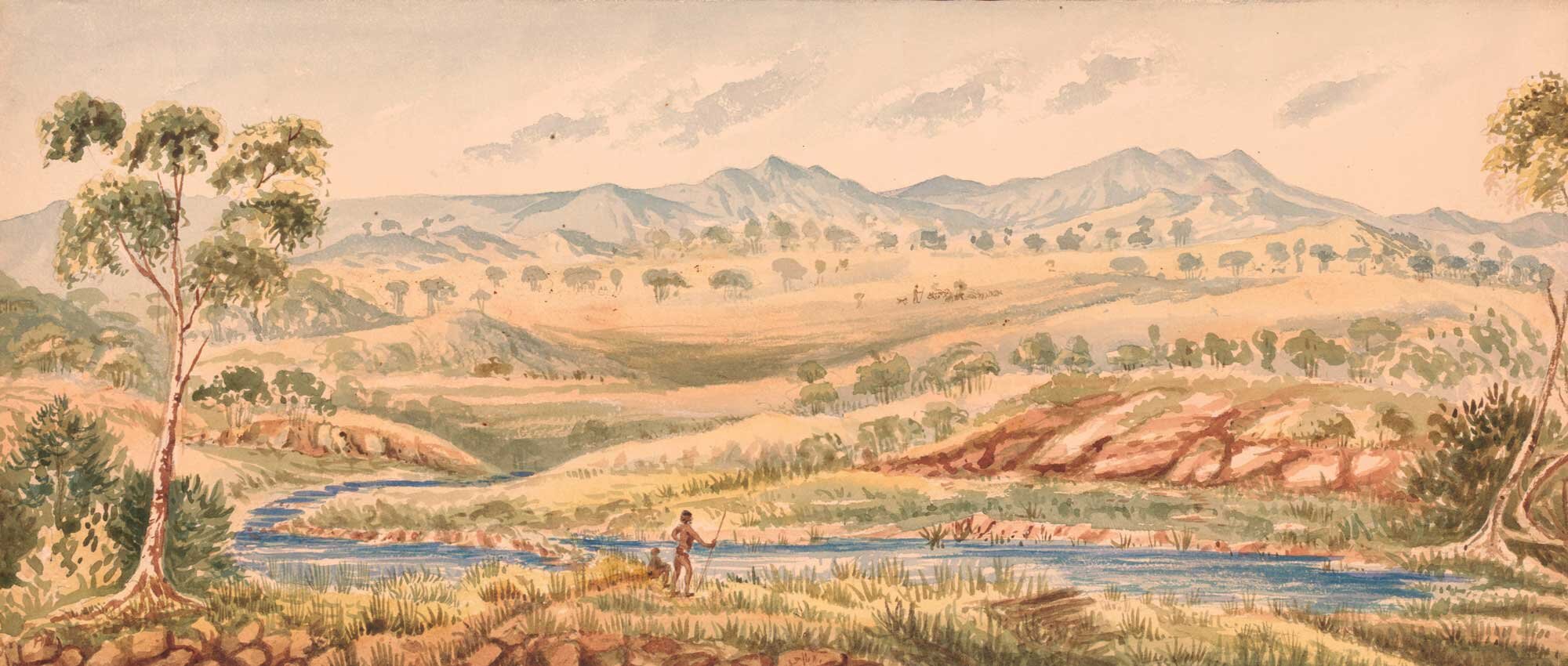

The first speaker, Bill Gammage blew my socks off! Bill has discovered, after more than a decade of research that at the time when Australia was first discovered by the Europeans, that the Australian Aboriginal people managed the land in a far more systematic and scientific way than we have ever realised. Bill’s examining of written and visual records of the early Australian landscape exposes an extraordinarily complex system of land management using fire or no fire to make distinct plant communities such as grass or open forest, or closed forest, and to associate these to protect species and to make resources abundant, convenient and predictable. In other words, they created the ideal environment for themselves living in a symbiotic and sustainable way with their fellow creatures and the land itself.

Yes people! in 1788, the Australian Aboriginal people were not aimless hunter-gatherers – they planned and managed the land. They ‘landscaped’ repeating a similar management template in a mosaic pattern around the continent, including Tasmania! What a revelation!!

“Australia was not natural in 1788, but made. Aborigines made it by using fire or no fire to distribute plants, and plant distribution to locate animals”

Why don’t more people know about this? Bill wrote a book about this in 2012 called ‘The Biggest Estate on Earth – How Aborigines Made Australia’, published by Allen & Unwin. Where had I been, that I hadn’t heard the discovery that the first, the best, environmental managers on the planet were the early Aboriginal people living in this country?! I knew about their special connection to the country, about their knowledge of using small, specific controlled fires to keep the country ‘clean’ and bring new life, rejuvenating the land, however, I did not know to the extent that they were maintaining diversity, ensuring abundance, balancing species, protecting habitats, all with great skill and discipline. Their whole way of living on the land was about sustaining rather than depleting.

Apparently, early European settlers would comment again and again that the land looked like a park or evoked a country estate in England. We’ve all seen the early paintings depicting the newly discovered pretty Australian landscape. I, like many others, assumed that these paintings were ‘wishful thinking’ or ‘projecting a vision’ of how early settlers were going to change the wild, rugged Australian bush into what these pretty pictures presented. Wait for it…..what Bill has uncovered is that these paintings were an accurate representation of what the landscape ACTUALLY looked like at that time. I’ll let that sink in…….

I learnt so much from each amazing speaker on the day, however, I have limited space on this broadsheet to cover every pearl of wisdom I received so I’m going to distill the essence of the message for you, dear reader.

When the Aboriginal people were taken off their country, they were unable to tend to the land and it became overgrown scrubland susceptible to enormously destructive bushfires that we now experience today.

We need to educate ourselves and connect with Aboriginal people and learn from their wealth of knowledge –basically the ecological standard that they had applied to the whole of Australia back in 1788. We’ve got indigenous knowledge on this land that needs and deserves to be held up.

“For Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders ‘Connection to Country’ was gained through eons of mutual relationships and the deliberate passing of knowledge. Today this living knowledge is available to City designers, to afford a more enriched authentic Australian way of living ”

How amazing would it be if we could instigate urban design principles with indigenous knowledge, working with country and their art of placemaking? Imagine if we had strategic frameworks for aboriginal engagement in urban development and environmental policy at a government level?! Of course, we mustn’t wait for those at the top, we need to make it happen in our own backyards first, and it has already started. Ros Moriarty from Balarinji spoke about their involvement with a development already underway for one of the largest road infrastructure projects in NSW, the upgrade of the Pacific Highway. She described how, “The Gumbaynggirr, Yaegl and Bundjalung people are sharing the rich cultural stories of their stretch of the Pacific Highway through a new way of connecting and collaborating.” The songlines that became Australia’s longest and most iconic motorway underpin the Aboriginal Cultural Masterplan for the Pacific Highway. Balarinji are exploring the parameters of the collaboration and what will be realised, what the landscape design opportunities are, what is important to the Aboriginal stakeholders plus so much more – how exciting and inspirational is it, that this conversation has finally begun!

As Greg Grabach’s thoughts on the day expressed, “The takeaway for me today emphasised the importance of nurturing a rich meaningful process in order to connect to Country. To take the fantastic highway upgrade as an example, the project in itself has become the vehicle/catalyst for change, not necessarily the outcome - which I am sure will be beautiful and engaging.

It brings back to the fore the age old philosophical argument between Parmenides and Heraclitus over perceiving the world as either a series of separate 'objects' or as a series of happenings, a process, or 'events'.

Like nurturing a democracy back to health we have to find a way to celebrate the process of participation, the layers of an art piece, the value in years of focused observation, the co-design process, the cleansing fire, the privilege of working together on 'Country'”.

Dillon Kombumerri spoke of the urban context of connection to country, “A connection to country for Aboriginal people is not just viewed as a commodity from which one can opportunistically benefit from – it’s like having a familial loving relationship between kin to be cared for and nurtured”. Dillon explained that memories and traces of our Aboriginal history are still present along waterways, in streets and public places we all share. If we fully embrace this knowledge it can influence the way we define and develop our future built and natural environment in a way, which makes us truly, belong, rather than just live in this great country of ours.

It is our responsibility to become connected to the Aboriginal community and their culture, so that together we can have a genuinely transformative Australian culture, and just as importantly, learn how to connect to country so we know once again what is forgotten…. That we are a small part of a much greater whole and that we must start sustaining rather than depleting our natural world. Let’s start dreaming together.

READS

Please do yourself a favour and read ‘The Biggest Estate on Earth – How Aborigines Made Australia’, published by Allen & Unwin.

We also recommend Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu, which builds in important ways on Bill Gammage’s book and now he has brought together the research and compelling first person accounts in a book for younger readers as well – ‘Young Dark Emu’.

pictured: ‘Young Dark Emu’, Bruce Pascoe.

Romantic Gardens Are Making A Comeback

This elegant home in Sydney’s eastern suburbs was a collaborative project between architect and interior designer.